New azhdarchid pterosaurs from the cosmopolitan azhdarchid family have been discovered in the Gobi Desert of Mongolia, expanding our understanding of flying reptiles from the Late Cretaceous period. These ancient creatures—Gobiazhdarcho tsogtbaatari and Tsogtopteryx mongoliensis—lived approximately 90 to 84 million years ago (Late Turonian–Santonian) in the Bayanshiree Formation, a region better known for its dinosaur fossils. Their discovery highlights the remarkable diversity and adaptability of azhdarchids, ranging from tiny species with wingspans under two meters to giants rivaling small airplanes.

Diversity of New Azhdarchid Pterosaurs

Pterosaurs ruled the skies from the Late Triassic to the end of the Cretaceous. However, their remains are extremely rare in Mesozoic Mongolia, unlike the abundance of dinosaur fossils found there.

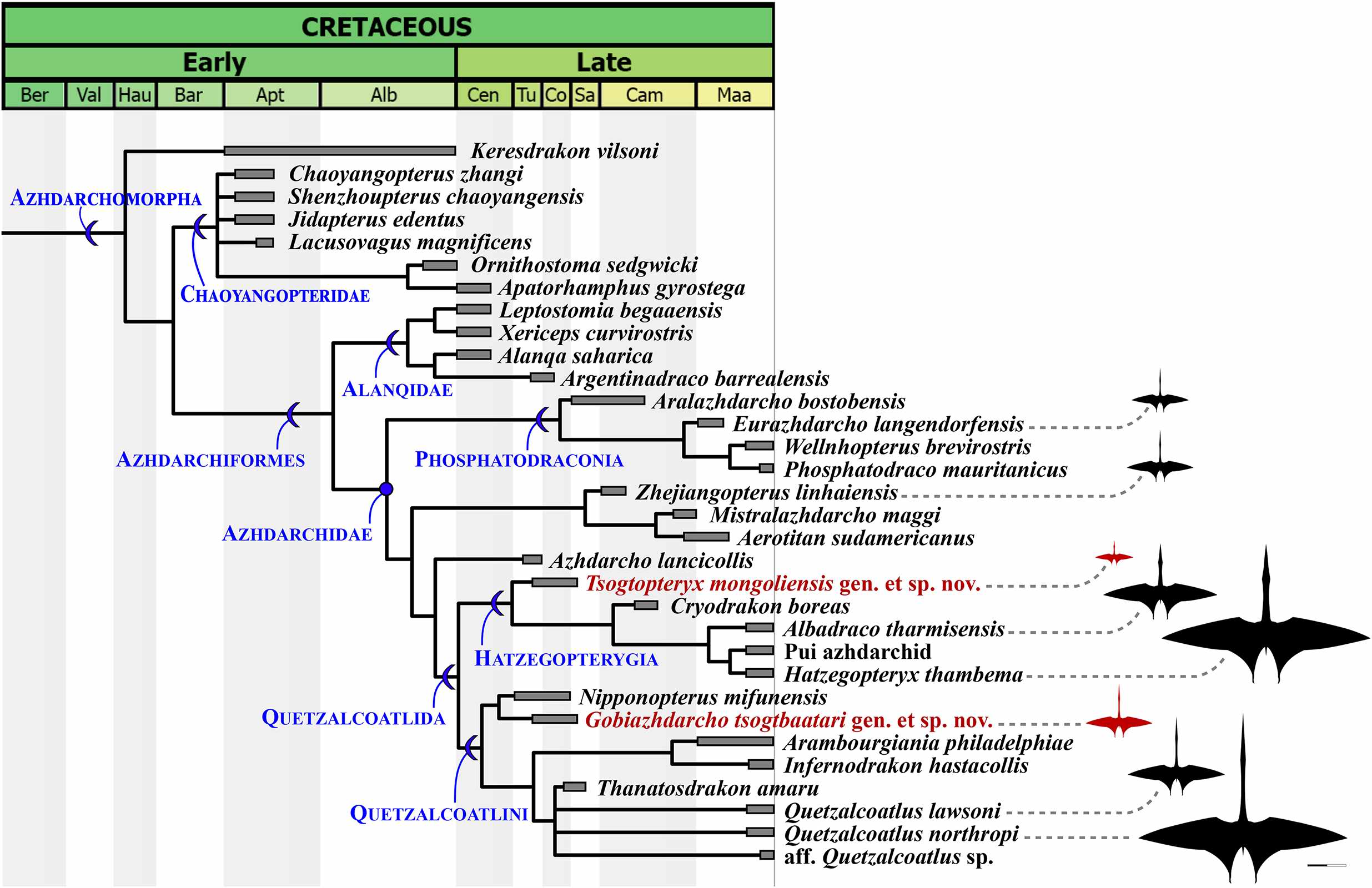

Azhdarchids were a family of toothless pterosaurs, recognizable by their elongated necks and long, toothless beaks. In fact, they thrived during the Late Cretaceous and were present on nearly every continent. Depending on the estimate, the family included between 17 and 22 species. For example, some, like Quetzalcoatlus, reached a record wingspan of 10–11 meters.

But not all azhdarchids were giants. The family also included medium- and small-sized species that likely filled various ecological roles. Unlike most pterosaurs that stuck to coastal habitats, azhdarchids often preferred inland habitats. Consequently, roaming floodplains and lakeshores in search of prey, they frequently hunted on the ground, leading a more terrestrial lifestyle compared to other pterosaurs.

Gobiazhdarcho tsogtbaatari: The Medium-Sized Flier

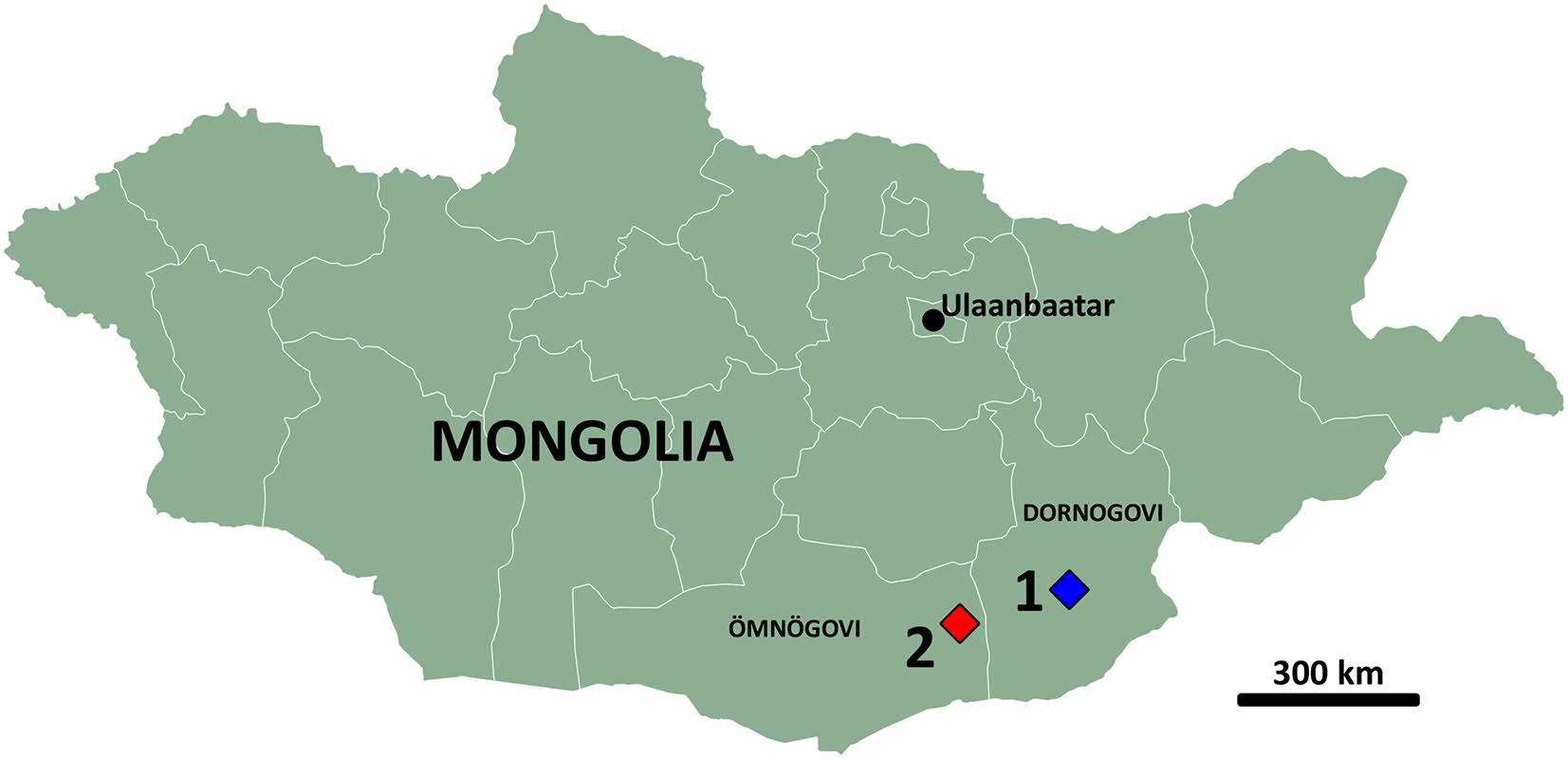

In the eastern reaches of Mongolia’s Gobi Desert, paleontologists have uncovered the first of the two new Mongolian species of pterosaur named Gobiazhdarcho tsogtbaatari. Specifically, discovered in Burkhant (Dornogovi Province), this prehistoric flyer had a wingspan of about 3 to 3.5 meters—roughly the size of a modern-day albatross, placing it in the middle range of the azhdarchid family.

Additionally, fossilized cervical vertebrae reveal features linking it to some of the largest pterosaurs ever known, including the famous Quetzalcoatlus and Arambourgiania, suggesting a shared evolutionary lineage. The genus name cleverly blends “Gobi” with “azhdarcho,” derived from the Persian word “azhdar,” meaning dragon. The species name honors renowned paleontologist Khishigjav Tsogtbaatar.

The specimen appears to have been a subadult—nearly mature but not fully grown. For instance, its anatomy reveals a long, slender neck, ideal for scanning open landscapes and possibly snatching up small prey from the ground. Like other azhdarchids, it probably preferred to roam floodplains and lakeshores in search of food rather than dive into coastal waters.

Tsogtopteryx mongoliensis: The Tiny Azhdarchid

In contrast, in the fossil-rich region of Bayshin Tsav (Ömnögovi Province), in southern Mongolia, another pterosaur turned out to be very different. Named Tsogtopteryx mongoliensis, it had a wingspan of just 1.6–1.9 meters, unlike its larger cousins. This makes it one of the smallest azhdarchids ever discovered. A middle cervical vertebra constitutes the known material of the species.

The genus name combines “Tsogt” (Mongolian for “mighty hero”) and the Greek “pteryx” (“wing”). The species name, mongoliensis, pays tribute to its Mongolian origins. Despite its small size, the specimen has cervical ribs fully fused to the vertebra, indicating it was an adult, not a juvenile.

This species belonged to a different lineage than its larger relatives. It was part of the Hatzegopteryx group, known for its robust and shorter neck. This discovery reveals that even within the same geological formation, vastly different types of azhdarchids coexisted—some towering giants, others nimble and compact, each likely filling distinct ecological roles.

Ancient Environment of the Bayanshiree Formation

Both species lived in the upper layers of the Bayanshiree Formation—clay and sandstone deposits formed in lakes and rivers in the eastern part of the Gobi Desert. During the Late Cretaceous, this was an inland region, far from the Eurasian oceanic coastline, much as it is today.

At that time, the area was semi-arid but included wetter environments. It supported a rich ecosystem of dinosaurs, turtles, crocodiles, and early mammals. For instance, ferocious predators like the giant raptor Achillobator stalked the same terrain as plant-eaters like Gobihadros, a duck-billed hadrosaurid. The presence of both large and small azhdarchids fits a pattern seen elsewhere in the world: pterosaurs of different sizes often lived side by side. Consequently, by targeting different prey and occupying distinct ecological niches, they reduced competition and thrived together in these ancient lands.

Phylogenetic Placement

The newly discovered pterosaurs from Mongolia belong to the broad group known as Pterodactyloidea—advanced flyers of the Mesozoic skies. These two species also highlight the evolutionary branching within the Azhdarchidae family.

Gobiazhdarcho tsogtbaatari traces its roots to the lineage of giants like Quetzalcoatlus and Arambourgiania—a group known as Quetzalcoatlini, characterized by long necks and soaring wingspans. Meanwhile, Tsogtopteryx mongoliensis belongs to the Hatzegopteryx group, which evolved shorter, sturdier necks and a more compact builds.

The coexistence of these pterosaurs demonstrates that two distinct evolutionary experiments in azhdarchid anatomy overlapped in time and space well before the end of the Cretaceous.

Conclusion

The new azhdarchid pterosaurs from Mongolia reveal that the skies over the Gobi Desert during the Late Cretaceous were far more diverse than previously thought. These discoveries—one a medium-sized species, the other among the smallest known azhdarchids—highlight the remarkable variety within the last great family of flying reptiles.

Source:

Researchers reported these findings in PeerJ and Acta Palaeontologica Polonica:

Pêgas RV, Zhou X, Kobayashi Y. 2025. Azhdarchid pterosaur diversity in the Bayanshiree Formation, Upper Cretaceous of the Gobi Desert, Mongolia. PeerJ 13:e19711 https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.19711

Mahito Watabe, Takanobu Tsuihiji, Shigeru Suzuki, and Khishigjav Tsogtbaatar. The first discovery of pterosaurs from the Upper Cretaceous of Mongolia. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 54 (2), 2009: 231-242 doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.4202/app.2006.0068